Author’s note: This article contains major spoilers for The Keep on the Borderlands, and minor spoilers for The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh.

Last week I complained loudly about The Last Train Out of Rakken-Goll for 3,000+ words. Since I need a break from negativity, this week I am revisiting a module I have much more fond memories of: The Keep on the Borderlands by Gary Gygax (1979). I adore this scenario, and despite some of its outdated design, I think there’s a lot to be learned from looking at it in retrospect in 2024. So, for this week’s article I will be looking into various aspects of the module’s design and asking these questions: What has aged well? What has aged poorly? What has aged…complicatedly?

Since it’s a bit unfair to compare a 40-year-old module to modern design standards, I won’t necessarily be going to much in depth on the module’s Clarity, Direction, Synthesis, and Reference. I don’t think it is controversial to say many modern modules are strictly better at all of these aspects, but that isn’t the point of this review. By the end of this article, we’ll address the most important question one can ask about a module: Does The Keep on the Borderlands succeed at helping the GM convey a plot at the table?

Premise

Keep on the Borderlands is a sandbox adventure module that puts the players in the titular keep, which is at the titular place. This nameless keep stands out as a beacon, holding its own against the forces of chaos (monsters, evil cults, etc.) while also attracting their attention. Players have come here to be rich and make a name for themselves, or so the module assumes. Nearby lies the Caves of Chaos, where Gygax assumed players would be spending most of their time. This is a rather (in)famous dungeon that a lot of people have complained about. It is assumed that by the time the players had cleared out the caves, they would be level 3 and move on to the GM’s homemade Cave of the Unknown.

That’s it, that’s the premise. The scope is limited to a keep and the locations near it. The encounters are limited to the classic D&D monsters (like, all of them), and the module is very clearly inspired (like many adventures of this era) by Sword & Sorcery as a genre, containing an evil cult that represents vague dark and evil forces.

Some Fun Artifacts of Its Time

There are some really fun artifacts of the time that are reflective of how new a genre ttrpg’s were at the time, and how much they have developed in the intervening decades. Most notable is that it is that the setting-wide conflict is between chaos and law. The evil cult doesn’t have any larger plans, it is simply a symptom of the forces of chaos. The monsters don’t have a larger plan, they are just an extension of chaos. This antagonism is treated more like a storm battering against a lighthouse (the keep) than some sort of narrative to unravel and defeat. The Keep just needs to stand against the waves.

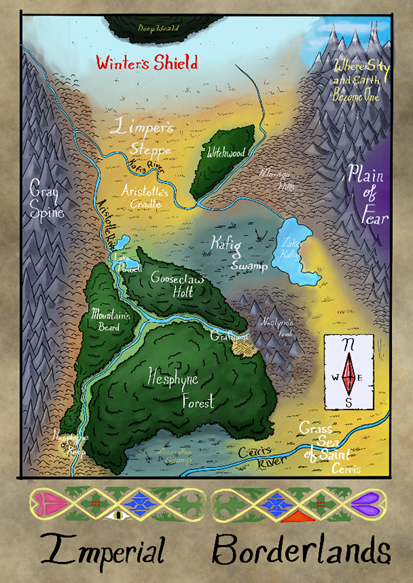

Also, man, look at this ugly map!

And of course, the map’s scale is completely bizarre, using a unit of 100 yards per square instead of the more typical mile, 1/8th mile, and 8 miles. This guy is just trying his best to be useful! The bizarre perspectives on the forests and the altitude lines are just sending me.

And of course there’s the art, giving us classics like:

Or this picture in the front cover where three heroes in poor perspective sorta just wail on an owlbear in the middle of a dungeon in a scene that can only be described as comical.

Anyways, nostalgia trip over, let’s look at how this adventure holds up and what it can teach us.

What Didn’t Hold Up?

The most obvious weakness of Keep is its poor layout. It’s blocky, and the headers aren’t apparent enough to help a reader differentiate between different parts of the text. It’s kind of like trying to count the number of zeroes in the number 10000008700000. Example of a full page from the adventure below:

You can also see that Gygax and TSR had yet to figure out how to demarcate descriptive text from mechanical and gm-facing text. And they wouldn’t figure this out until The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh. Example of Saltmarsh’s innovative and important contribution to adventure layout history is below:

And now compare it to Keep on the Borderland’s again:

The difference is night in day. Keep is just harder to quickly find details and information because early RPG creators did not understand what constituted strong instructional design. Nowadays publishers use different variations on Saltmarsh’s demarcation technique to differentiate between text types and purposes. You can actually see the influence the influence most prominently in D&D’s latest (and my 2nd favorite) edition. Just look at this passage from Wild Beyond the Witchlight.

The boxed text delimiting description and mechanics was a very strong solution to Borderlands’ hard-to-skim layout, and I am not surprised that Wizards of the Coast continues to employ it to this day.

Author’s note: If the box text actually predates Saltmarsh, let me know! I’m curious, but Saltmarsh appears to be the first do it based on my limited knowledge.

Another weakness of the module is its hooks. As a starter adventure, GM’s simply expect better hook suggestions. Compare Keep’s “go to the Borderlands to seek glory” hook to Witchlight’s “You all went into the carnival without a ticket, and lost something valuable. You feel incomplete, so you’ve returned to the carnival” hook, and two things are clear:

- Adventure-specific and character-driven hooks are much more in-vogue these days.

- We’ve gotten much better are writing interesting hooks.

This is not to say that seeking out glory and money are bad motivators for characters to have, or for GMs to state, but most consumers of modern RPG products are going to expect stronger hooks that tie into a central narrative. This was one change I made when running Keep on the Borderlands. I created hooks that tied in my players’ characters to the larger political situation in my campaign world, which afforded me a chance to pursue a stronger theme than killing monsters because it gives you money and glory. (My players also fought many monsters for glory and money!)

Speaking of layout and the text within, the detail in many of the descriptions is a bit excessive. Each room description lists gold coin amounts, equipment, spells known, etc. This information may have been useful for Gygax personally, since much of his DM advice and “running the town” suggestions boil down to advice for making your players take the game seriously. I have no doubt his player characters were running around the keep like a bunch of animals stealing anything they could get their hands on. They were Conan fans, dammit, and they probably really liked Deathstalker (terrible movie, great soundtrack) too! But I think most people these aren’t really playing that kind of game anymore.

Also, each NPC completely lacks a name since Gygax assumed the GM would just figure it out. Fortunately, we have moved into an era of better design.

One of the modules major failings, and something to pay attention to in our own design, is to do with diversity of his NPCs. Out of every single listed NPC in the module, there are no women that are not wives. Zero. Well, okay, there’s a Medusa who betrays you, but that really drives home the point further. Every NPC is assumed to be a man. This is bad design. If you are going to design medieval fantasy (or any genre involving working class people, really), it is important to remember that the working class is incredibly diverse. I work in manufacturing for my day job, and there is no other field where you fill find a more diverse group of individuals coming together to make something. Doesn’t matter who you are: if you can do the work well, you’re going to be put to work.

Next time you’re writing a module, please make sure to pay attention to incidental and accidental biases when creating NPCs. Maybe you make too many men? Maybe all of your characters are Tieflings? Maybe they are all cis and straight? I’m not trying to be the fun police here, but it is important to point out that a diverse cast is simply more realistic, and we make ourselves better GMs when we identify our own creative biases and patterns.

My obvious suggestion, if you are determined to run this module, is to make some of the NPCs women and nonbinary. This will make your world more realistic. Nonbinary captain of the guard sounds cool to me!

What Did Hold Up?

While age has not been entirely kind to Keep, there are some elements that have really held up quite nicely.

The A-Plot and B-Plot

The module has a sort of hidden A/B Plot structure that has a lot of flexibility. As the players murderize their way through the Caves of Chaos and get gold and glory, they will uncover a secret cult that has spies within the keep. There are lots of little seeds of this plot around the keep and the surrounding area, the agents of chaos are constantly spying on the keep, looking for weakness. For the B-plot the players are assumed to use their hard-fought gold and glory as a means of gaining access to Inner Bailey of the keep. Thus, access to the Castellan, and more importantly, status. People in the keep will trust them.

Although Gygax does not provide much depth and direction for running these plots, the two really intertwine nicely, and an experienced GM should be able to turn this framework into something really interesting.

The Proto Sandbox

Speaking of things the GM might need to flesh out a bit more, the setting likewise is ripe for a good sprucing-up. There’s a mad hermit, some bandits, and a lizardfolk tribe all working in tandem with the forces of chaos (intentionally or otherwise). So if your players get bored of running around the Caves of Chaos or the Caves of the Unknown, why not throw some lizardmen at them? I ended up expanding the borderlands quite a bit for my setting, although I kept all of the basic elements: the cult, lizardmen, bandits, and the cave. I did add a town and tried to eventually seed in Red Hand of Doom (if you look at the regional layout of my map, it is remarkably similar to the map from Red Hand). But by the time we got to RHoD, I was pretty burnt out and instead ended the campaign with an epic fight against the chief cultist/wizard of the caves.

Here’s my version of the borderlands, for those curious:

If you are looking to learn what a good sandbox adventure looks like, Keep is definitely a great example of this. I might as far to say it is the proto example of what a sandbox adventure should look like. It has random tables, maps, key locations, and a narrative that connects all of these points together. This is certainly a step up for Village of Hommlett. A better sandboxes could and have been written since (Raging Swan’s Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands comes to mind), but Gygax’s OG Keep really has this magical feeling for me whenever I’ve run it. I really hope to come back to this adventure one day and run it more by-the-book in AD&D, or in whatever edition for some newbies. Really make ‘em sweat their spell slots.

What Held Up…Complicatedly?

The Caves of Chaos are a bit of a meme at this point. Yes, we all know they don’t make sense, but they are also a great place to adventure. The players will have to learn to negotiate with some of the monsters, it’s the only way they can survive. And you can seed in a bunch of different hooks in different parts of the caves. They’re mega-dungeon adjacent. This all being said, they still make no sense, and I think I know one reason why:

The gorge, the iconic visual of the caves, is my biggest problem with this dungeon. It is either a) a death trap or b) a quick connection between the disparate parts. People often complain that everything in this dungeon is too close together, but it’s not the physical distance that is the problem, it’s the psychological distance. Dungeon crawling just takes longer to move through than gorge-walking. If the gorge was instead a maze of rooms and the such, I feel like a lot less people would be ragging on this dungeon for its cramped tribal politics.

Although Keep’s dungeon layout and design is weird, the module does a really good job of tying the drama of the keep into the Caves. So, basically, you’re stuck with them. This isn’t a dungeon that can be easily lifted and replaced unless you want to completely redesign it from the ground up.

Conclusion

Gary Gygax’s legendary module, The Keep on the Borderlands, has aged better in some ways than others. Modern designers can learn from some of the design choices, both bad and good, and it is also a nice peak back to the days when the roleplaying hobby was still developing. Still, two questions remains:

Does it help the GM convey a plot to their players:

Yes! Absolutely! It is a serviceable sandbox with some nice background plots in there for a dedicated GM.

Is it worth picking up nowadays?

This is a harder question, but ultimately, I would say yes with an asterisk. If you are looking for an example of historical design and want to run something for a short game with a storied and memorable dungeon, I would probably pick Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh or Cult of Reptile God before I picked up this module. There are many better-designed sandboxes such as Veins of the Earth, the fifth edition Ghosts of Saltmarsh (its chapter on the region is super excellent), and Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands. Still, Keep on the Borderlands does provide a GM with almost everything they need to run an interesting game. If you are keen on picking up this module, the print-on-demand version is available from DrivethruRPG in print + PDF for $12. I don’t think I would spend more than $15 on Keep, considering all of the other good modules that are available to GMs nowadays. An original I can say, without any doubt, it is much much better than The Last Train Out of Rakken-Goll.

Advice for Running It

If you’re dead set on running this module, here is what I recommend doing in order to elevate your experience:

- Do your own region map and expand the wilderness. At the very least make travel to the Caves of Chaos take longer than a few thousand yards. This will put the fear of God and trees into your players, which is essential for capturing that old school feel.

- Flesh out the Cult plot and the Castellan, know their names, motivations, and fears.

- Track the influence of Cult throughout the adventure in some way. What do they want from the Castellan and the members of the inner bailey?

- Make the inner bailey a huge deal.

- Emphasize the political nature of the Caves of Chaos. Alliances may shift and change, and loyalty is hard-fought.

- Figure out if you want to go with the Law vs Chaos theme or insert a campaign theme of your own. Understand how the Keep connects back to the rest of the wider campaign world (not just the region).

- Come up with your own random tables for the Keep that emphasize your campaign themes.

- Make your NPCs gender diverse. About half of them should be women if we’re going by real world statistics.

Anyways, that’s all I have to say about The Keep on the Borderlands. I hope you enjoyed this article. Next week I will be taking a look at reworking the Universal World Profiles from Traveller with an eye towards accessibility and readability, and some journal thoughts on reading and running my Curse of Strahd campaign or fifth edition Dungeons and Dragons.

Will Strahd finally be able to understand what tech level is? What does the Starport of Ravenloft look like? And should Barovia’s political code be a monarchy, or something else entirely? Find out next time!

Leave a comment